(An essay on The Daughter of Kumari, originally published in Tamil, Kurugu, Dec 2025)

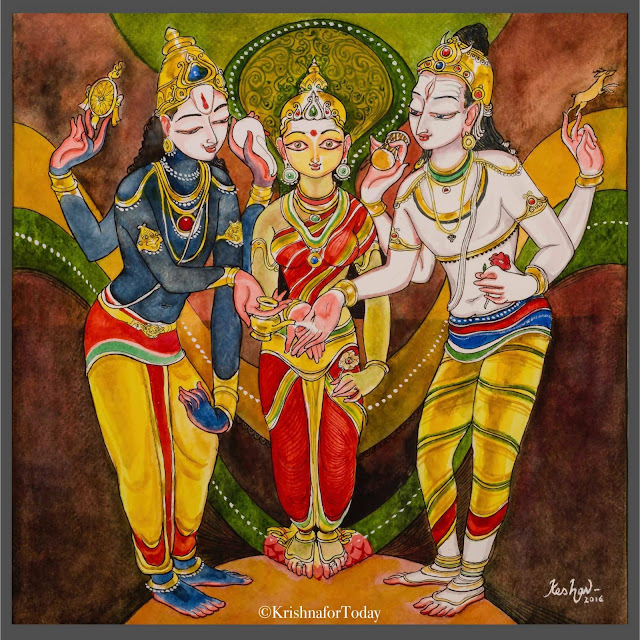

When gods play with men, then can’t men play with the gods too? Both plays happen all the time. One play reflects the other, like images in a mirror, multiplying endlessly. The gods are creatures of endless, boundless play. They play with us, they play us to play stakes with them too.

So ends the short foreword that Jeyamohan wrote for The Daughter of Kumari.

Mirror reflections that proliferate endlessly. If god and human are the two mirrors, then what is the play that unfolds? It is this quest that sets The Daughter of Kumari apart as a creative work that goes beyond the limits of post-modernism. It is a work of an emerging new age.

It will be an interesting journey to trace how the notion of the deity is depicted through the various historical movements in literature. For example, we could imagine a modernist text, one that a quintessential modernist like U.R. Ananthamoorthy might have authored.

A deity emerges in a village. The deity exercises influence on the people and makes them worship it. It commands them, extracts offerings and sacrifices from them. But over time, differences begin emerging between the deity and the people. The people of the village are not able to meet the endless sacrifices demanded by the deity. The march of human life courses past the deity, making it obsolete. Bereft of worship, the deity is gradually abandoned. In the end, it stands there, having become a mere idol of stone.

What is an idol? A word that has lost its meaning. There is one detail in particular that we need to attend to in this story. The modernist story begins with the premise of faith of the pre-modern age. It paints a picture of a movement towards a splendid loss of faith. All great literature is a record of such transitions and movements. The account of the modernist observes with sincerity, at the same time, both the bitterness and the freedom of this shift from faith to faithlessness.

But what endured after the shift to modernism? Literature, naturally, resorted to talking about empty idols, with words deprived of meaning. This was in fact the prison that modernism had shut itself in. And, it was from there that post-modernism began its course.

The post-modernist movement began with the modernist premise of faithlessness. We can extend our metaphor by going back to the village and its deity. Now that their deity has become a mere idol of stone, the people experience a profound meaninglessness that engulfs their lives. Out of sheer boredom, they pick up the idol and start performing rites and sacrifices. It soon spirals into a spectacle of distraction. The marketplace and carnival quickly find their place in it.

The tragedy of modernism has now turned into a post-modern farce. From high seriousness to a comedy of errors. An empty play of signifiers. It is, in a way, both a deep reflection of the loss of faith, as well as a shallow display of their lack of it. When everything flattens to a surface, terms like depth and superficiality, like all others, lose their meaning and distinction.

But the story does not end there. We can imagine a further culminating act. Amidst the endless entertainment, the playful rites of sacrifice bring the deity back to life. Its stone lips part. From its speech, words regain their meanings. Things become enchanted again.

Yes, we have now come to the end of our parable. We have completed a full circle. We have found God again. But all rediscoveries are brand new too. The sand and dust of our trodden paths brings new experiences that profoundly influence our discoveries. We have, thus, moved from a ‘talking god’ to a ‘responding god’. A God dialectic.

*

In discourses regarding God in western philosophy, this movement from the post-modern has been anticipated with prophetic clarity by a distinct tradition. Tracing through philosophers like William James, Henri Bergson, John Dewey, we reach its summit in A.N. Whitehead’s distinctive ‘process philosophy’. In his work Process and Reality (1929) – one of the central philosophical texts of the early twentieth century – Whitehead remarks: “God’s purpose in the creative advance is the evocation of intensities.” Two elements are worth noting here.

Firstly, the unconventional expression, intensity. Not good, not order, none of the motivations we tend to identify with the purpose of a traditional god. Intensity.

Most importantly, the judgment of intensity is not just moral but also a deeply aesthetic one. In Whitehead’s philosophy, it means plurality, richness, fluidity, beauty of contrasts and many other things. Note that Whitehead is not talking about the harmonising of contrasts but the beauty of contrasts. And in Whitehead’s language, the expression ‘beauty of contrast’ is superfluous. According to him, all contrasts are beauty, and all beauty contrasts. The continual transposition of oppositions into contrasts is the sublime act of god. Contrasts are, thus, points of intensities.

In a land without god, what we lose primarily is this intensity. Or we can rephrase the statement slightly to better persuade the atheists. In all that we feel as intensity, an element of the divine gently comes to reside.

The second element crucial in Whitehead’s statement is that, in his view, god is not the sole creator of the world but only a pole in the process of creation. One of the two mirrors held to each other. It is through dialogue that it creates.

Here we confront the voice of the atheist. How can a god ‘invented’ by man speak? Haven’t we already deconstructed the fact that god, like so many other phenomena, is merely a social construct?

The most significant moment in the philosophical thought of the late twentieth century is movement from deconstruction towards constructivism, observes Bruno Latour. If it is that things are not autonomous but constructed out of a web of social relations, constructivism begins precisely from this premise. It makes it its study the archetectonics of such construction. How it is that a constructed ‘thing’ seems to gain a voice of its ‘own’. If self, freedom and all the various references to the conditions of subjectivity are so constructed, how different is god who could demand the same existential import? It is a common expression in English to say, ‘Well, it’s a thing now’. What do we truly mean by that? It means that various assemblages can become a thing, where a thing is fundamentally understood as something that can produce an effect outside of itself. Philosophically, anything that has causal efficacy could be considered a thing. It is not necessary that it is simple and non-composite, in fact we learn that no-thing is non-composite. Here again Bruno Latour observes how the etymological origin of the word ‘thing’ has its roots in the ancient idea of assembly. The ‘idea’ of God is in the same way an assemblage of meanings and significations as is a chair, without which it is merely an uninteresting geometric structure without purpose. When two members enter into a promised agreement, it becomes a ‘thing’. We immediately come to perceive that it has a moral force of its ‘own’. The fact that it depends on the two members who entered it and that the idea of a promise (as a moral duty) is a socially constructed one, does not make it any easier to nullify its effect (It is precisely this element that drives the last act of The Daughter of Kumari). If such is the case, a ‘constructed’ god too can have a voice of its ‘own’. It too can participate in a dialogue.

On the other side of the spectrum we hear the voice of a traditionalist, ‘How could god-created-beings enter into a dialogue with its own creator? Change it?’ — for to enter into dialogue truly is to affect and be affected by it.

Whitehead observes elsewhere evocatively, “God is the poet of the world”. Though this analogy is a traditional one, a deep look into the creative process reveals an understanding that could help answer the traditionalist objection. Characters that are entirely under the power and control of the poet who created them turn out to be lifeless. Living characters are always those that respond, resist the poet’s authority and enter into a dialogue with him. A poet who holds omnipotent sway and power over his work creates characters that are dead, and in the process, heralds his own death.

A sculptor is passively responding to the demands of the sculpture as much as he/she is actively sculpting it. It is mostly the ventriloquist voice of fundamentalists that sounds through a god that is projected as impervious to the demands of the human need.

All this suggests that there can be a true dialogue between god and human. It is this dialogue that fills the world as the multitude of reflections from the two mirrors held to each other. In this creative bursting forth of reflections, it is meaningless to search for the first voice that arose. Let the theists and atheists bang their heads against such trivialities. As William James puts it, “Does the river make its banks, or do the banks make the river?” The bank guards; and the river flows. In final analysis, the passionately argued stances of theism and humanism merely stand in this arbitrary relation. Here we stand as staunch realists, our feet firmly planted on the ground. Ours is not a non-committent position of an agnostic. Our commitment is most rigorous, attentive to the finest realities of the world and its state of affairs. It is then that we will observe that there is an ideal that constantly responds to the aspirations and needs of humans. It is not absolute, lest it stagnates, neither is it ever-changing, lest it loses its power. Eternal and fluid it plays with us. Justice and mercy are its twin faces.

*

Any reader of The Daughter of Kumari will immediately come into the effect of its emotional intensity. It is in the realm of feeling that it primarily reveals to us its vision of god, and indeed its vision of the human too.

The story begins with a modernist premise. Set in a very particular historical period, effected through a completely determined chain of events, the idol of Meenakshi (and it is very much an idol here) is brought into the kingdom of Venad. In contrast to the timeless eternity of myth, the historical grounding of the story is well-defined in the novel. The dialogue between this temporal unfolding and the eternal forms the essence of the work. As soon as the fundamental conflict of the story arises, a re-enactment of mythology, a hieros gamos, is proposed as a possible resolution.

In Hindu mythology of South India, the holy marriage of Meenakshi and Sundareswara is seen as the union that offers legitimacy and authority to all human marital relations. In The Daughter of Kumari, the order of operations is reversed. It is now humans who stand witness to the divine.

But what makes Kumarithuraivi a modern literary work is the deep irony that it holds within its premise. Even at its most dramatic, we are intensely aware that it is an idol that is at the centre of it all. Or even strangely, it is precisely the irony that produces high drama here. Not modernistic cynicism nor post-modernist laughter, here it is irony that reinstates emotional intensity. Throughout the text, the author intermittently uses the passive voice to describe the movements of the idol thereby constantly reminding us of its objecthood. In an age when we witness our most cherished things rapidly turn into empty idols, here is a literary work that performs the miracle bringing an idol back into life; and the moment this idol turns divine forms its denouement.

It is a simple yet powerful plot device that operates here. In the final act, the narrator, holding god as his witness, makes a vow staking his own life. The moment he made the vow he knew, that it was something beyond the control of both himself and the man who sought the vow. But the rules of the game had been laid out. Leaving the fateful dice in the hands of God, our protagonist waits.

The game defeats him. The grand event that he so meticulously helped plan stumbles by a slight human error. What was promised must now be accomplished. Even the man who demanded the vow wants to let it go, saying that it was spoken in haste, that it was all a bad dream. But it was a game that was played with God as witness, it was a game played with God itself. What was at stake was his very life. It was the moment to bow one’s head before pitiless justice.

It is here that god speaks. Through a glorious turn of events, human error becomes divine intervention. It is the ultimate deus ex machina. God has now entered the machine, turning things upside down. What was flawless until then now turns imperfect, and what was flawed now attains purity, turns auspicious. The dice did not change, the rules did. At the heart of every grave predicament, there enters a great mercy that erases the lines, modifies the rules, and liberates the soul.

The dialogue reaches its peak here. Human and divine, action and passivity, justice and mercy switch places. A god all too human, human all so divine. It is moments like these that we call creativity. The history of the world is measured by moments of such creativity. And in each of these, there lies a play, between the human and the divine. Creativity is nothing but a radical new interpretation of the rules of this game. A game that the divine plays with each individual and with the whole of humanity at the same time. There is no ideal that a human can hold that is absolute, singular, overpowering. It is changeable, plural, merciful, precisely because it is ideal. It is a God that bends a little and comes down to us whilst we sink in despair.

An open, free God, bound not by self imposed grandeur but by compassion. The God of endless creativity. A merciful God blessed by all creation!

The Daughter of Kumari

Jeyamohan

Translated from the Tamil by Suchitra

Purchase link: Amazon

You must be logged in to post a comment.