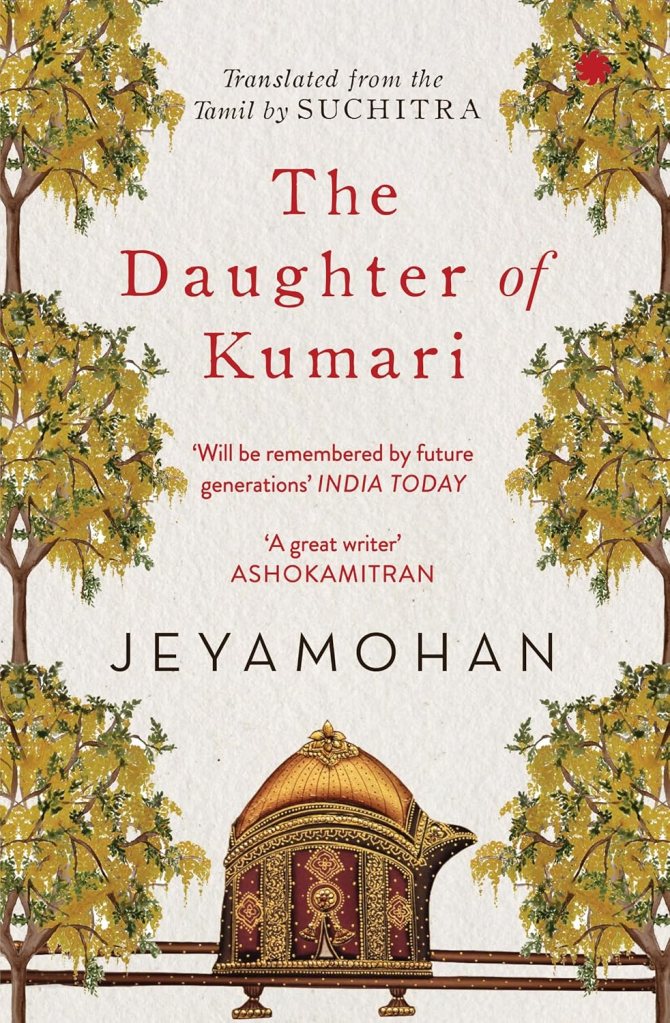

Jeyamohan’s The Daughter of Kumari, my English translation of his Tamil novel குமரித்துறைவி / Kumarithuraivi, was published recently.

Purchase link: Amazon

From 2014 to 2020, over a period of six years, Jeyamohan wrote a modern Tamil epic, a novel series called Venmurasu based on the Mahabharatha. A creative re-narration of the classical epic, Venmurasu draws on the archetypes of the Mahabharatha, as well as various pre- and post-Iron Age classical and folk narratives to create a layered, highly complex narrative that reinterprets India’s philosophical, religious, social and political history for the modern reader. He wrote this novel series every day for six years, publishing a chapter a day on his website before they were published as physical books: 26 novels, over 25,000 pages in all.

I began reading Jeyamohan when he started publishing Venmurasu. Following such an epoch-making feat in real time has been a surreal experience. Jeyamohan followed up Venmurasu, whose final chapters were published around the time of the first Covid lockdown, with a spree of short stories, also published on his blog every day. For 136 days, his readers followed along as he published as many short stories, light-filled little gems and literary bonbons that seemed otherworldly in their narrative ease and depth of vision. He concluded this long braid of storytelling with a perfectly crafted fish-shaped tail-piece, almost divine in its conception: Kumarithuraivi.

The story is about a king who has to return the idol of a goddess (Meenakshi) who, during a period of historical exile, had ‘chosen’ to stay in his land (Venad, near Kumari). The difficult emotions around the return of a goddess who brought only auspiciousness to his country permeate the story. It is not difficult to read a prolifically creative writer’s angst in the tale: seven years of near-constant highly creative expression were drawing to a close when he wrote the novel.

The story resolves this emotionally charged conundrum in the most gracious way possible: by staging the goddess’s return as a wedding, the divine wedding of Meenakshi with her handsome lord Sundaran of Madurai. The king plays the role of Meenakshi’s father, giving her away to the Nayakas of Madurai, not as conquest, but as blessing and benediction. Although grounded in 14th century CE historical realism, the tale acquires the cosmic grandeur of a divine comedy, as it reveals the everyday role-play between the gods and humans and the blissful necessity of their emotional entanglement.

A work of great benediction and grace, Kumarithuraivi recreates the myth of Meenakshi Kalyanam — the celestial wedding of Meenakshi – that is still celebrated yearly during the summer month of Chithirai (April – May) in Madurai and other places. It was a story that absolutely captivated the hearts its Tamil readers when it came out. The archetype of Meenakshi as beloved daughter, always leaving, yet always staying, moved the people who knew the goddess and her tale. The new setting and premise secured its place in the firmament of tradition as almost a new purana, a mangala-kavya. The book is being translated into Telugu, where I am sure it would find similar favour with the readers, since the two languages share a similar cultural space where Meenakshi is entirely familiar and beloved.

As soon as it was published in Tamil, I sought permission from Jeyamohan to translate the novel into English. He graciously agreed, but wondered whether the emotions of the novel would find resonance in the Anglophone reader.

It is difficult to characterise one typical Anglophone reader, but from reading contemporary Indian writing in English, one could not be faulted for assuming that the English reader expects prose in an understated style, with restrained emotions and a removed ironical eye that sweeps over its characters and marks them in their places.

Moreover, when one readers contemporary literary writing in English, it feels like religion is examined only in relation to its politics. I’m struggling to think of a recent Indian fiction originally written in English that looks upon religion — any religion — historically, aesthetically, spiritually, emotionally, even socially — anything except politically. On the other hand, we have sentimental tellings and modern re-workings of religious themes in the highly popular bestsellers of the day, some of which come loaded with their own politics and agendas.

In such a milieu, how would the reader receive a work like The Daughter of Kumari, that fits into neither of these boxes? Would the urban Anglophone reader relate to the immediate emotions around fathers and deities and daughters in a way a culturally “grounded” Tamil or Telugu reader might? These were some of the questions Jeyamohan posed.

I think these questions are real and important. But, as I told Jeyamohan, I believe the only way to know the answer, or even bring the question up for discussion, is to translate a work like Kumarithuraivi and have it published in English. When discussing questions of style or themes or readership, it always helps to have an example at hand – an example that the discerning reader can pick up, read, ponder over, discuss, compare and come to their own understanding.

*

I believe that there is no one typical Anglophone reader today. I feel that the urban, upper class, English speaking reader with no roots with local culture is as much of a stereotype as the ‘dehati’ reader who reads in the bhasha languages and has no idea about what high culture or literary values are. I think that we are finally at an age when we can knock these silos apart and start having real conversations around our literatures, our styles of expression. Translating various styles of writing and talking about them, in parallel with Indian writing in English, might get us there.

With this background, I’d like to make a few points about Kumarithuraivi’s style, and especially its irony. There is an irony in the telling of The Daughter of Kumari, but it is not the kind of irony — superior, removed — that we are used to in contemporary writing. There are two kinds of irony: a ‘small’ irony, that reduces the subject of the ironical gaze in the eyes of the reader, and a ‘greater’ irony, that, by describing its object in acute detail and detachment, gives the reader a penetrating, palpable insight into the character being observed. The second kind of irony does not reduce the character in the concentrated heat of the writer’s superior gaze. Rather, it brings out for the reader what is real and true and essential in the character, and invites a kind of empathy from the reader because of how true and palpable the character is in that gaze. Shakespeare is a master of the ‘greater’ irony. He draws Polonius like an irritable, hypocritical, slightly ridiculous father, we even smile at his speech to Laertes. But we nevertheless ‘know’ him through that brief interaction well enough to grieve at his unjust death.

It is the second kind of irony that can be found in The Daughter of Kumari. The king, the foolish minister and general, the guests and officers, even the idol of the goddess herself is examined with such an unsentimental, yet palpable irony that endears us to them. [More about the irony in The Daughter of Kumari is discussed in this essay, included in the book: Twin Faces, by Ajithan J]

The prose style of The Daughter of Kumari is not something the average Anglophone Indian reader might immediately find familiar. The first chapter, with its profusion of names and historical details, sets the realism in place like the granite stone foundations of a South Indian temple tower. The novel opens up for the reader who crosses that gate. The novel is told through the first person narrative voice of the proud, principled erstwhile nobleman protagonist, Veeramarthandan Udayan, a chief administrator officer in the minor medieval kingdom of Venad who is tasked with orchestrating the wedding.

What stands out for the reader is the grounding of the novel in historical time, while simultaneously being modern in its perspective. Veeramarthandan Udayan is an administrator of his time and place. He is as religious and feudal as a man of his time can be presumed to be. But his eye roves through the people and actions unravelling around him with a certain measured ironical detachment that the modern reader would entirely relate to. He is often impatient with those officers who don’t match his wits, ambitions or efficiency. He is even a little cynical at times. But never is he a misanthrope or a nihilist. Even with his big ego, he is possessed of a single-minded earnestness that forms the backbone of the narrative. The historically staged play becomes a divine comedy and a cosmic event because of the depth of his earnest, searching gaze that is able to see through the apparent nature of things to its otherworldly meanings.

The narration is entirely realistic, at times bordering on the naturalistic in its description of details. But there is always a transcendent evocation in the mildest of detailing.

Here is a scene that details how flowers are strung in preparation for the wedding:

It was dark outside. Dawn was still some time away. Fresh buds and blossoms had starting coming in from all over the country. But the lotuses and other flowers for the morning worship would only be plucked at dawn. Four hundred and fifty marar women were stringing the flowers together into garlands. I imagined their fingers to be little weaver birds. They kept stringing and weaving without rest. Heaps of flowers to one side, the garlands they were coiling into, like many-hued serpents, on the other. The scents of that place plucked us from all earthly concerns and hurled us elsewhere. Only flower scents suggest that beyond everything of the world, there exists something else altogether.

Here is another passing description of dawn, on the morning of ammai Meenakshi’s departure.

The darkness of dawn hung heavy in the air. Every single thing was slowly emerging from the dark, coming alive, joining hands, locking eyes with something else, and together creating the morning. By light, they were making themselves one. No, not by light, it was not light yet. This was just a faint glow. Just a revelation – rather, only the hint of one.

In this telling, an everyday dawn becomes an extraordinary event, just by deepening the gaze of one’s perception. The rather pudgy word ‘dawn’ resolves into the first light by which objects come into existence and create the morning. Then it resolves ‘light’ even further, into a ‘faint glow’ and further into a ‘revelation’ and even further into ‘just the hint of one’. An everyday dawn tales us back to the first moment of creation when the hint of a revelation arose – the revelation that created and became all the world and existence. And then the twist in the realisation hits us – that this revelation happens everyday, at every dawn. The extraordinary is nowhere else; it is here, now, everyday, all around us.

The way the prose of The Daughter of Kumari brings together the ordinary and the extraordinary was the greatest challenge in translating it. Jeyamohan has composed his Tamil original with an extraordinary economy and precision of language, but one that looks apparently simple and elegant. It’s like making jewelry in granite as if it was gold. Kumarithuraivi, published in 2021, is a slim book, about 200 pages in length. It took me the better part of four years to create and revise the translation. While effort went into sourcing arcane vocabulary and the names of various objects that go into the creation of an earthly-yet-celestial wedding — I did feel from time to time like Veeramarthandan Udayan, as if I was riding around the countryside sourcing words like he searched for materials to make the wedding complete — the greater part of my effort rested on creating an English prose that could approximate the strength, range and ease of the original Tamil.

I cannot say that I succeeded entirely. When I look at the book now, I only see my errors. I see only what I could have done better. It only brings helpless tears. But in a strange way, it is also comforting. An entirely perfect work, if it exists, would be like a block of stone with no room to breathe. The imperfections and flaws of a work are where another hand might come in, to make it better, to fill the gaps. When I look at this translation now, it reveals my own humanity to me. Both the human loftiness of spirit that undertook such a task, and its inherent limitations. Strangely, the thought frees me of distress, as if the hand of god is upon my head.

My hometown is Madurai. My ancestors have served in the temple there. People in my family still exclaim ‘Meenakshi!’ when they face any calamity, from a death of a child to stubbing their toe on furniture. Something of that spirit still lingers in me, I suppose. So, I say now, as I float this attempt at capturing the divine beauty of Kumarithuraivi on the river of time, with hope and goodwill that it finds its readers — Meenakshi, your grace.

The drums that struck up like a thunderclap roused me to my senses. Before I could turn around, the sivacharyas had pulled aside the curtain. A synchronous cry of wonder rose from the audience.

I was looking on, my hands clasped. I felt water roll down my cheeks, my nose choked up from all the tears welling up inside. Meenakshi sat there, as if she was herself all the light in a diamond. She wore diamonds everywhere – on her hair balled up into a bun sloping to the right, on the crest-jewel on her forehead, in her ears, around her neck, down her bosom, at her waist, on her hips and encircling her lap. There were diamonds on her feet. All her fingers and toes were ringed with diamonds. The parrot in her hand was all diamond too – its wings were diamond, its beak was diamond, and its eye, too, a diamond.

It was as if she had become a single diamond herself. Sundaresan, who sat next to her bedecked in a similar quantity of diamonds, seemed pale beside her. Her face looked like copper on fire. As if it would melt in a moment and a drop of the red-gold metal would fall to the ground. What was that fire inside her? I had seen it earlier, on the faces of newly-married women who were to leave their parental homes and go away with their husbands. Long eyes, intoxicated with madness. Red, as if in a fever. As if in a frenzied trance. The same fervid madness appears in the eyes of women after their confinement too, when they have just been delivered of a child.

The Daughter of Kumari

Jeyamohan

Translated from the Tamil by Suchitra

Purchase link: Amazon

You must be logged in to post a comment.